How important was postage stamp propaganda in the establishment of Soviet Russia?

Since the introduction of the Penny Black in 1840, the postage stamp has been used as a prominent canvas for pushing political and cultural agendas. Stamps have frequently been adorned with the faces of monarchs and other political leaders. Other common subjects include cultural landmarks, key historic figures of the nation, and nationalistic imagery. In this essay, I will investigate the role of Russia’s stamps in the establishment of the Soviet Union and communist political and social ideals.

The Russian Revolution

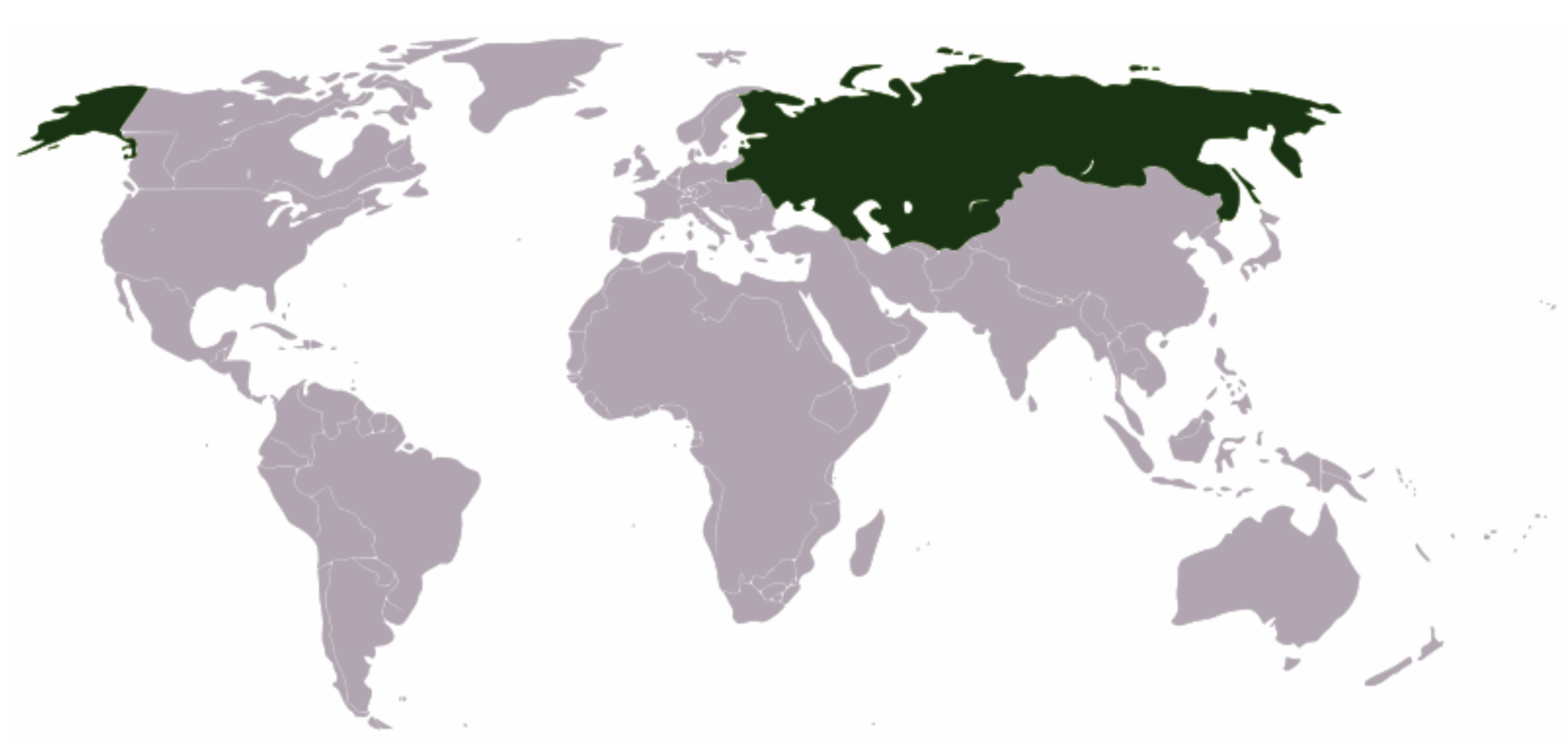

Figure. 1 – The Russian Empire in 1917

From 1721 the Russian Empire, ruled by the Tsars (Russia’s emperors), was one of the largest empires of world history (see figure 1). Prior to it’s collapse in 1917, it was one of the five dominant powers of Europe, and held sway over 125 million people. However, the economic and social disparity of the empire meant that by the early 20th century, many of its populace were angered and dissatisfied with their lot. These conditions, amplified by the horrors of the First World War in 1914, set the stage for the Russian Revolution.

The 1917 Russian Revolution was a series of uprisings against the Russian monarchy of the time. These revolutions eventually led to the establishment of the Soviet Union, a socialist political system based on communist ideologies.

The breakdown of the Tsar’s power occurred in two key stages: during the chaos of a large uprising in what is now known as St. Petersburg, the Tsar abdicated and was replaced by the incapable Russian Provisional Government. In the infamous October Revolution, the Bolshevik party, led by Vladimir Lenin, overthrew the Provisional Government. The Bolsheviks appointed themselves the leaders of Russia and it’s various Government ministries, and eventually signed a peace treaty with Germany, earning increasing their support.

Unrest and civil war continued for several years, but eventually the Bolsheviks were able to consolidate their power, and thus the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR) was established (later becoming the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

Pre-Revolution

Russia has had a fairly long relationship with the postage stamp. Stamps were officially introduced across the Russian empire in 1858. From then until the Russian revolution of 1917, thirty-seven unique stamp designs were produced. They were consistently decorated with important Russian heraldic imagery, most notably the seal of Tsarist Russia and its double-headed eagle. The imperial eagle was first introduced in the late 15th century, and remained an important symbol for the royal families, until their downfall 450 years later.

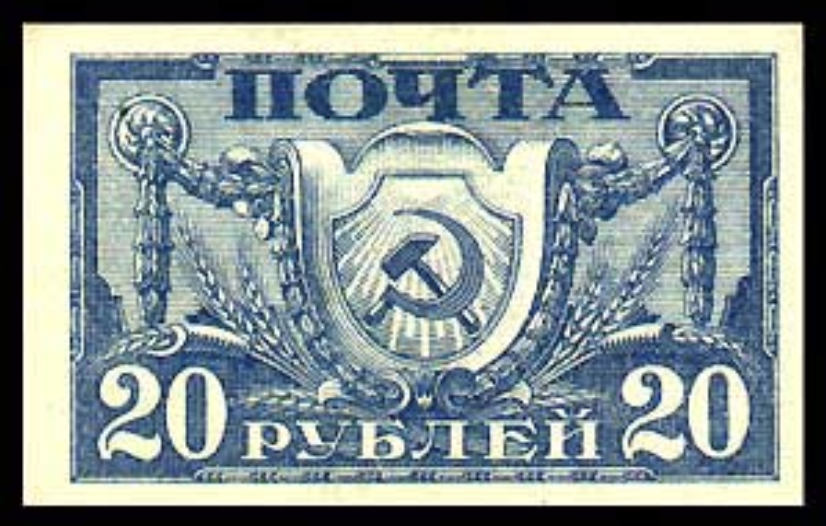

These first stamps were treated very much as government documents. Their primary concern was with the establishment of a reliable currency, and therefore preventing the creation forgeries. Design principles were very much borrowed from banknote design. The stamps born of this mindset are small, featuring intricate and complex patterns, often in multiple colours (see figure 2). The printing techniques used, and even the type of paper available, resulted in an entirely different result to the stamps used today.

Post-Revolution

When the Tsar was overthrown in August 1917, much of Russia’s infrastructure and services were thrown into disarray. Authority was devolved to individual post offices across the various nations of the empire. As formal governance was restored, the state began to rapidly expand its network of post offices. This push was focused primarily on rural areas, especially in the Central Asian Republics (e.g. Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, etc.). Approximately 75% of these new offices were located in rural areas that previously had limited or no service[3]. This sort of inclusion was an important symbol for prioritising the common man, and ensuring that the necessary service of communication was available to all, and garnered much support for the party.

A result of the expansion of the postal network was that many more people were exposed to stamps. Suddenly, the postage stamp had vast potential throughout Russia as a propaganda medium – after all, it was being handled by many millions of people on a day-to-day basis. Despite this potential, it was not until late in 1918 that new editions were produced – the old Tsarist designs were simply reprinted during this transitional period, but were non-perforated and often disfigured. Even when new editions were produced, pre-revolution stamps remained in circulation.

Figure. 2 – A 1918 re-issue of a pre-revolution design

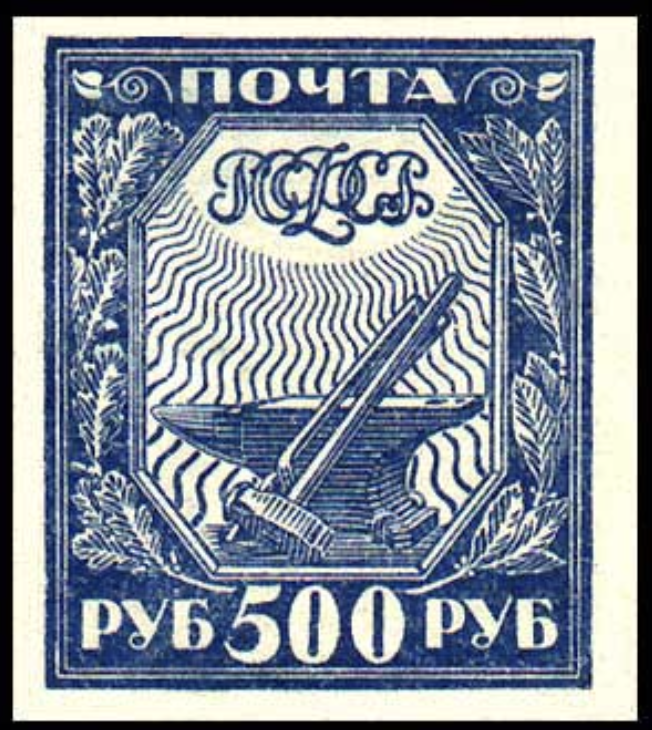

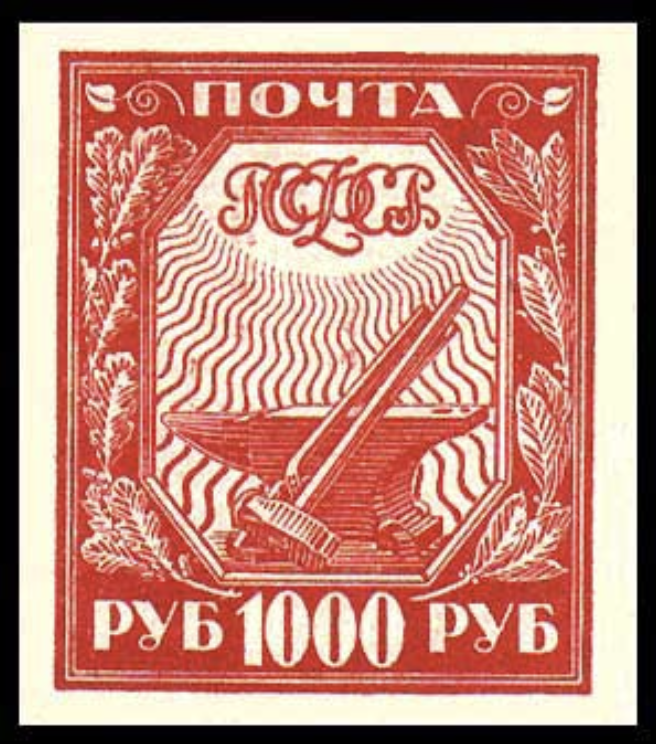

Figure. 3 and 4 – Post-revolution stamp designs issued in 1918

When the new editions were released in 1918, gone were the imperialist images of old. The first set of stamps of the newly established Russian SFSR were particularly poignant (see figure 1). Both stamps portrayed a sword of the revolution freeing Russia and its people from the chains of the oppressive Tsarist regime.

The following set of stamps, released in 1921, were less about the events of the revolution, and more about the representation of communism, and the aims of the new government. These new stamps began to introduce the emerging visual language of communist Russia. The emphasis on the tools of the working populous – the hammer and sickle – replaced the more flamboyant coat of arms of the Russian Empire. The new crest of Russia - as well as the hammer and anvil imagery - conveyed the communist message of the power and the importance of the working class. They also represent solidarity and reliability, an important asset after the disruptive upheaval of previous years.

Figure. 5, 6 and 7 – Stamps issued in 1921

As is shown can be seen in the stamps so far, an initial change in the production of stamps was that, from 1918 until late 1922, all new stamp issues were monochrome. The most common colours were, perhaps surprisingly, blue, followed by brown, and orange. Monochrome stamps were simpler and cheaper to produce, but easier to forge. Most stamp designs prior to the revolution were bichrome, featuring two, often contrasting, colours. One final trend that stamps track is the huge rise inflation in Russia during the 1920’s. As inflation grew, sur-charges were added to stamps (see figure 8). These take the form of the iconic the hammer and sickle within a five-pointed star.

Figure. 8 – Old stamp sur-chaged for inflation Figure. 9 – A memorial stamp for Lenin

The Death of Lenin

Despite the vast changes sweeping across Russia during this period, stamp designs remained extremely traditional. Having removed the traditional Russian imagery from stamps, officials seemed content to continue producing stamps in the conventional style. However, when Lenin, the iconic leader of the revolution, died in 1924, and a radical stamp was released in commemoration.

This hugely modern design was a brand new approach to the design of stamps. For the first time in Russian history, the postage stamp was treated primarily as an object of propaganda. The bold design forwent traditional security measures used on stamps, and was therefore very easy to forge.

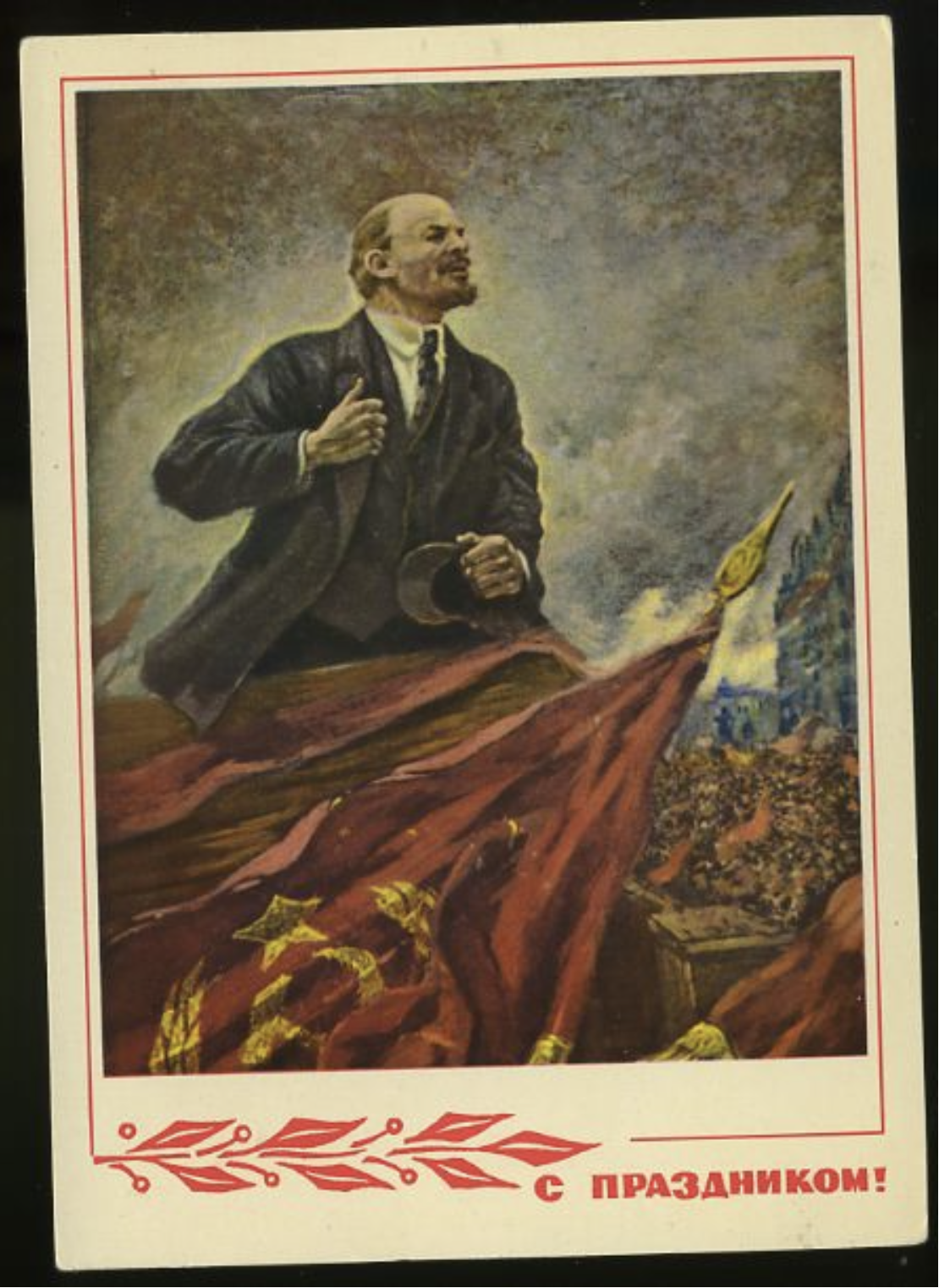

Figure. 10 – V.I. Lenin on a tribune – a popular propaganda postcard

Indeed, this change in the government’s approach to the stamp was confirmed by the vice minister - “Postage stamps have become, in the years of Soviet rule, miniature works of art that reflect the events or our epoch and have commanded wide respect”[1]. Over 50 billion stamps were printed over the first forty years of Soviet rule, and was thus one of the most far reaching of propaganda mediums. For the first time, the visual effect of the medium was more important than its practical qualities.

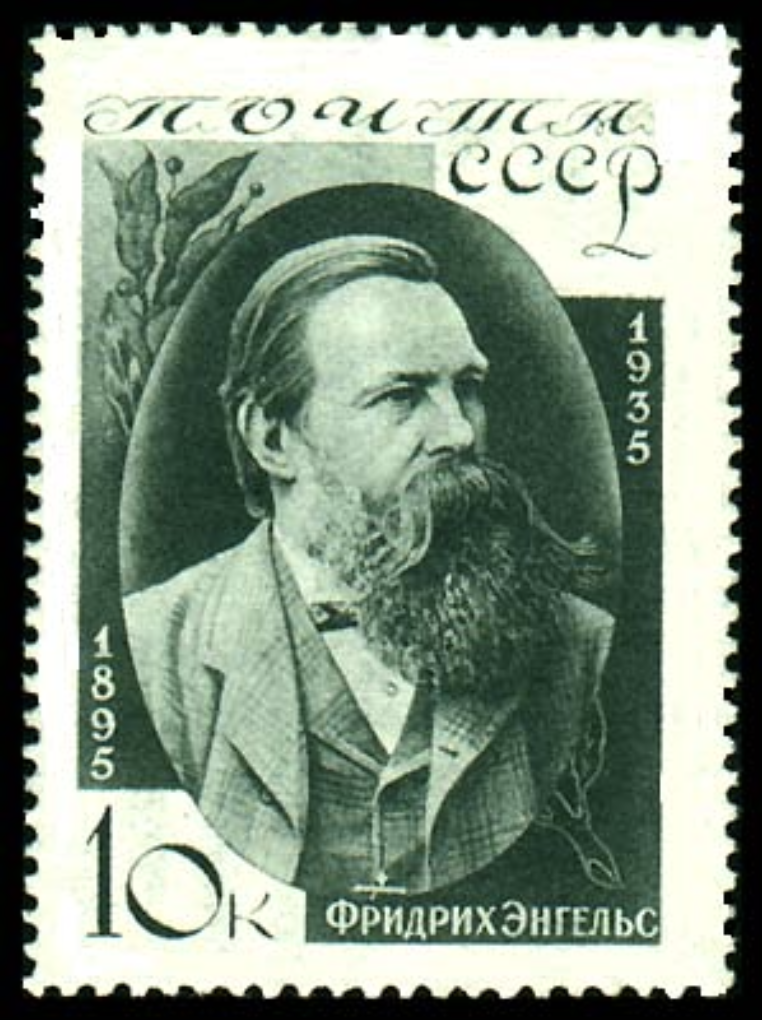

Stamps issued in the following decade maintained elements of this bold graphic style, primarily in the typography and ornamentation. However, the key new development was developments of portraiture in philately. Advances in both printing and image creation techniques led to a huge rise in the depiction of humans upon stamps (see figure 11). This allowed the government to create figureheads of communism – idols and model communists for the population to look up to and see as a good example. This move was vital is maintaining support of communism as an ideology, and in maintaining the legitimacy and popularity of Russia’s leaders.

Figure. 11 – A stamp depicting Friedrich Engels

The stamp was not only a propaganda tool in its own right, but was also a supporting medium for the famous Soviet propaganda postcards (see figure 10)[4]. As is typical of many of the Soviet government’s institutions, Russia’s postal service became increasingly inefficient[2]. A delivery that would have taken a mere two days in 1858 could take up to ten days in 1958. Whereas the concern of the early postal service was efficiency and reliability, the emphasis on design may have eventually harmed the postal service

Figure. 12 – With Lenin – a popular propaganda painting and postcard

Conclusion

Ultimately, the postage stamp was important in establishing the new socialist Russia. It was key in carving out the distinctive communist visual identity. This identity was crucial in defining the objectives of the communist government and gathering support and solidarity during a troubled period on European history. The stamp, combined with the postcard (see figure 12)[4], was key establishing Lenin as the key cultural figure of communism that he became after his death. This identity was important in the longevity of communism in Russia, and Lenin was revered alongside Karl Marx and Freidrich Engels (authors of The Communist Manifesto) as a father of communism. Their faces adorned many a stamp over the following century[5][6].

Bibliography

- The Landscape of Stalinism: the Art and Ideology of Soviet Space

- Soviet History in the Gorbachev Revolution – Robert William Davies

- http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/472092/postal-system/15435/Italy#toc15436

- Postcards from Utopia: The Art of Political Propaganda – Andrew Roberts

- http://www.stamprussia.com/lenin.htm

- http://www.stamprussia.com/communism.htm

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Postage_stamps_and_postal_history_of_Russia

- A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1917-24 – Orlando Figes

- The Russian Revolution – Sheila Fitzpatrick

- The Communist Manifesto – Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels